Reflections: On Harmonising Natural Capital & the Human Economic Sub-System

Geoffrey Matthews: Civil Engineer, Municipal Engineer and Natural Resources Management Specialist with the World Bank for 14 years, Geoffrey is International Consultant for "Development for Sustainable Survival" - a process which promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources to maximise the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems.

It is my opinion that Professor Dieter Helm‘s keynote video presentation introducing the SSA’s 25 Year Environment Plan response event (March 2018) signals the end of the 66 year opportunity to implement ‘sustainable development’; and the beginning of a 25 year challenge, set by the British Government, to institutionalize and operationalize ‘development for sustainable survival’. Survival implies a choice of life and death. It gives the task in hand a sense of urgency and brings the objective into sharp focus. To survive, every living organism on this planet needs to eat, drink and breathe every day. Yet we are polluting and depleting the vital life-supporting natural resources that enable us to satisfy these needs: soil, water and air. The estimated number of remaining harvests says it all: fewer than 100 harvests mean many children born today will struggle to survive to the end of their natural life.

We cannot say we weren’t warned. The scientific community, major NGO’s and the UN have made us aware of the risk of natural resource mismanagement for decades - for example:

1962: Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring - Warnings on pesticide use

1977: UN Conference on Water – Assessing water resource issues

1980: The World Conservation Strategy - As relevant today as when first published

1982: Exxon internal report predicts global warming

1987: Our Common Future - The World Commission on Environment & Development, presided over by Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, brings the concept of Sustainable Development into focus. It is described as a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, direction of investments, orientation of technological development and institutional change are all in harmony, enhancing both current and future potential to meet human needs and aspirations.

Relevant key concepts: Global Ecological Overshoot; Limits to Growth; and Ecological Economics.

Multiple international conferences have also attempted to help sustainable development gain traction.

As soil is at the core of civilization, as Professor Helm reminds us, all these contributions to guide development on a non-destructive path could have been employed to ensure the healthy management of soil: but, alas, they were ignored - not only by farmers but also politicians, agribusiness and the financial community. Indeed, it’s strange that some in the farming ‘business’ are consciously destroying their own vital natural working capital. They have exchanged survival ad infinitum for ecocide within 100 harvests.

Achieving harmony: A systems perspective

To avert this catastrophe one can analyse Brundtland’s description of the process of sustainable development from a systems perspective, with the objective of achieving harmony between nature and humanity.

Nature is, by definition, Planet Earth's Natural Capital Economic System. It is the world's stocks of natural assets upon which humanity depends entirely. As defined by the Scottish Forum on Natural Capital Management these assets include geology, soil, air, water and all living things. All living things must include humans.

The conservation of the natural capital economic system is therefore vital, because it is a question of survival.

Humanity represents the Human Economic System, a sub-system of the Earth’s System (Daly, Jackson). For it to survive it must be the agent of conservation of all natural capital, because if the Human Economic Sub-System’s demand exceeds the capacity of the ecosystem to regenerate the resources it consumes and absorb its wastes, ecological overshoot will occur - thereby debilitating the inventory of natural assets.

It’s also important to note that it is impossible for the human financial community to lend money to natural capital.

The fundamental financial tenet of survival

The Earth Systems perspective validates the imperative that farmers’ revenue should be dictated by the real cost of production on the farm side of the gate. This is because the farmers’ natural working capital is a part of the Earth’s Economic System, and the farm gate is the de facto “interface” between the Earth’s Economic System and the Human Economic System. So, because it’s the farmers’ responsibility to conserve their natural capital in quality and quantity ad infinitum their revenue must be equivalent to the full cost of conservation and production ad infinitum: anything less than this will be a systemic disaster.

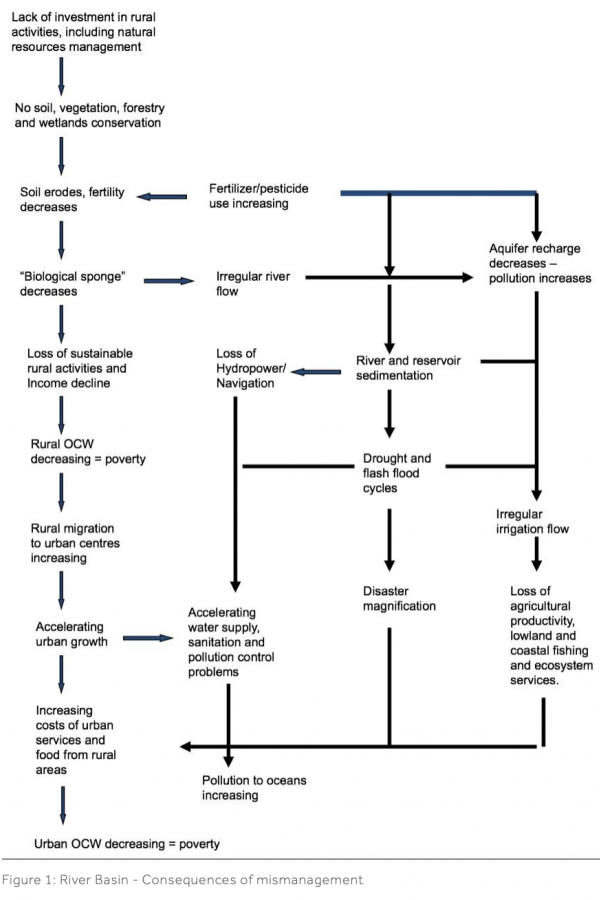

Unfortunately, it is patently obvious that this fundamental financial tenet of survival is ignored globally. The result is illustrated in Figure 1: River Basin – Consequences of Mismanagement. This figure, which incorporates several of Professor Helm’s points, shows the effect on the downstream environment of the lack of investment in rural activities and natural resources management at the head of the river basin. It results in the decrease of rural and urban Overall Creditworthiness (OCW).

The impacts of declining Overall Creditworthiness

The elements of OCW assessment, i.e. attractiveness for investment, are social capital, economic capital, environmental resource capital, water capital and financial capital. OCW is the embodiment of knowledge, commitment, administrative management and communication capabilities; environmental resources, services of the ecosystem and the economy, goods, property, soil, water and finance. All these components are tangible and can be universally understood. For example, a river basin which has depleting mines, eroding soils, deforestation, diminishing genetic diversity, increasing vulnerability to natural disasters and climate variations, advancing deserts, polluted or declining soil and water resources, air pollution, mismanaged aquatic resources (wetlands, rivers, lakes, oceans), unskilled people, weak institutions and little ability to service debts will be considered by the investment community as being less attractive for long term financial support. This decline in OCW will feed back to the head of the river basin and unless something is done to reverse the investment community’s consideration, OCW will continue its downward spiral. This is not healthy for a country, the financial community, the planet and the survival of the human species.

This is not an exaggeration. A farm is a microcosm of Earth’s Natural Capital Economic System. It is a finite quantity of soil, biodiversity and water, the quality of which dictates an optimum production capacity. Infinite growth is therefore impossible. However, due to negative financial pressure from the Human Economic Sub-System’s global food market in the form of imposed prices for farm produce, the farmer is obliged to try to increase the production area of the farm within the limits of the property in order to survive financially. Biodiversity habitat within the farm is the first to be sacrificed. Then, driven by the fear of losing a harvest, exacerbated by the vagaries of the climate, more and more agrochemicals are applied to the soil. These are detrimental to the health of its biodiversity: soil quality begins to fall and ecological overshoot occurs. Consequently, yields decrease to the point that the farmer is unable to support their family and bankruptcy ensues, resulting in rural desertification of soil, water and social capitals. So goes the farm, so goes the planet, and with it both current and future potential to meet human needs and aspirations.

It follows therefore that, if the recommendations of the Brundtland report are to be realised, Planet Earth’s Natural Capital Economic System must be conserved in a resilient, healthy “Steady State” (Daly) in terms of quantity and quality ad inf., with sustainable financing ad inf.

Achieving the Steady State

Step 1: Decide the size at which Earth’s System must be conserved.

Global Footprint Reports show that since the 1970’s growth-driven development has caused ‘Global Ecological Overshoot’ (GEO) to increase from zero to 50% (the GEO being the difference between the annual demand for natural capital from Earth’s Natural Capital Economy, and the capital the planet can generate). I propose, therefore, that the size of the Earth’s Natural Capital inventory to be conserved ad infinitum should be that of the 1970’s.

Step 2: Select a financing instrument which will be sufficiently robust to ensure sustainable conservation financing ad inf.

The current institutionalised financial instruments are inadequate for arresting the decline and destruction of the Natural Capital Economy because they have reached the limit of their effectiveness, e.g. tax saturation, debt ceiling (97% of all money in circulation is speculative, i.e. debt); and, as already mentioned, it is impossible for the Human Sub-System to lend money to the environment to conserve the Earth’s System. Relying on the private sector has also proved to be ineffective as witnessed by the continued widening of the GEO. Consequently, budgets for the management of biodiversity, air, soil, water, education, and health are inadequate.

Sovereign Money for Conservation

At present conservation and restoration activities depend mainly on unpaid farm work, charities and volunteers, and they all do fantastic work. However, their work does not pay the rent or mortgage, put food on the table or contribute to a pension. Sustainable Development for Survival cannot be considered a hobby: it has to be a business.

To avoid further debt, inflation and austerity, the only financial instrument which is suitable for funding the conservation of the Earth’s Natural Capital Economic System is Sovereign Money. The institutionalization of Sovereign Money dedicated solely and specifically to conservation and restoration will make the Natural Capital Economy independent from the Human Economic Sub‐System and therefore resilient to the vagaries of politics, the human financial system, the global food market and natural disasters. At a country level, Sovereign Money for the Conservation of Sovereign Natural Capital will contribute to National Security.

Sovereign Money would be emitted by a Central Bank and regulated by a national Natural Capital Economy Monitoring Committee. Sovereign Money for Conservation would not transit the private financial system and it would not be a loan. Consequently, it would be debt free, thereby avoiding any increase in the current debt load, austerity, inflation and taxes. The value of this investment for survival would be the Earth’s Natural Capital assets.

To avoid speculation, “Sovereign Money for Conservation should only be created from hours of conservation work done” (Fisher), including the hours required for inspection, paid at the rate of a ‘Living Wage’ directly to the author of the work. The Living Wage should be index-linked to the real cost of living. Considering the amount of conservation hours to be worked, a considerable amount of money will be created. The receivers of the Living Wage will have the choice of investing in either the Natural Capital Economic System or the Human Economic Sub-System.

The objective should be to turn conservation in to a global business that is more lucrative than the current process of destruction. The institutionalisation of Sovereign Money for Conservation by every country’s Central Bank, including all the countries in the Eurozone, would make this possible.

Establishing the new system

The institutionalization of Sovereign Money for Conservation should begin on-farm. Firstly, the Soil and Water Capital conservation work executed by the farmer, including the work required to mitigate flooding caused by runoff from the farmland, will be registered as ‘hours-worked’ and paid accordingly via a personal account at the Central Bank. This will be the farmer’s primary income - independent of the sale of produce, it will support the farmer every year, meaning in the event of crop failure or low market prices there will be some protection against financial ruin.

Secondly, income derived from the sale of produce to the Human Economy will be the farmer’s secondary income. The price in national currency should be equal to the production cost, including maintenance of an acceptable quality-of-life for the farmer. If income at the farm gate is insufficient to cover the cost of on-farm conservation, the farmer can apply for Sovereign Money for Conservation.

Both incomes can be used for the acquisition and maintenance of machinery and other inputs from the Human Economy. Alternatively, as the Living Wage is index-linked to the real cost of living, ‘conservation hours’ could be archived as ‘savings’ and cashed in when required, for a pension for example.

With regard to situations outside the control of the farmer which can pollute the farm’s soil such as water and air pollution from industrial sources or other Human Economy activities, Sovereign Money for Conservation could be used to stop the pollution at source; and, assuming the polluter-pays system fails, then be used to depollute the farm. Existing contaminated water and soils on- and off-farm could be cleaned up with the same funding mechanism.

Sewage and sewerage is another example of an opportunity to operationalise development for sustainable survival on a global scale. There are many human settlements worldwide which have no sewage treatment facilities, so one could imagine countries could launch a programme of projects funded primarily by Sovereign Money for Conservation, to start immediately.

Systems in Harmony

To make Sovereign Money for Conservation palatable for governments et al, perhaps one should present the monetary system of the Human Economic Sub-System and Sovereign Money for Conservation of the Earth's Natural Capital as being complementary. Essentially the idea would be to permit the traditional development process to continue and institutionalise Sovereign Money for Conservation to fund a conservation and restoration business to depollute soil, water and air. Every debilitation of the Earth’s inventory would be a conservation/restoration business opportunity. At some point the two systems would be in harmony as desired by Brundtland and money would be earned positively on both sides.

If Development for Sustainable Survival and Sovereign Money for Conservation could be institutionalised and operationalised now, survival could be assured within 25 years.

Geoffrey Matthews - Lyon 26/10/18

Recommended reading:

Beyond Growth: The economics of Sustainable Development Herman Daly

Prosperity without Growth: Foundations of the Economy of Tomorrow Tim Jackson

Master Currency Sustainable Economic System Rodney A. Fisher

What Matters? Economics for a Renewed Commonwealth -

Essay: Money versus Goods Wendell Berry with forward by Herman Daly