Soil is widely considered to be the Cinderella of environmental issues, neglected by governments and other stakeholders when it comes to investment, regulatory protection, monitoring and education in comparison with air, water, trees and biodiversity.

So why is it that soil lags so far behind these other indicators of the state of our environment as a political priority?

There are numerous reasons. These include the perceived complexity of soil, and a reluctance by governments to ‘interfere’ with what is a farmer’s private property. Soil also rarely features in public awareness campaigns so there is less political pressure to act.

But the critical difference is money. For a generation, environmental policy has been driven by EU Directives (Air, Water etc.) which gave the EU the power to fine Member States for non-compliance and failure to hit targets. The threat of fines provided the impetus for policy intervention, targeted mechanisms (education, regulation, guidance etc.) and most critically - investment.

The 2014 EU Soil Framework Directive could have been the trigger for policy interest in soil, but it was withdrawn by national governments in 2017 – the only EU Directive ever to be abandoned in this manner.

Without a Soil Framework Directive, no threat of penalty has hung over the UK government, enabling soil to be discreetly de-prioritised at every level – and a lost decade for soils. Over this period there have been no tangible soil targets or thresholds because of the lack of a baseline understanding of soil’s health. The lack of a baseline is due to the absence of nationwide monitoring, and the lack of monitoring is due to a lack of funding thanks largely to the absence of an external EU threat needed to focus minds and justify investment.

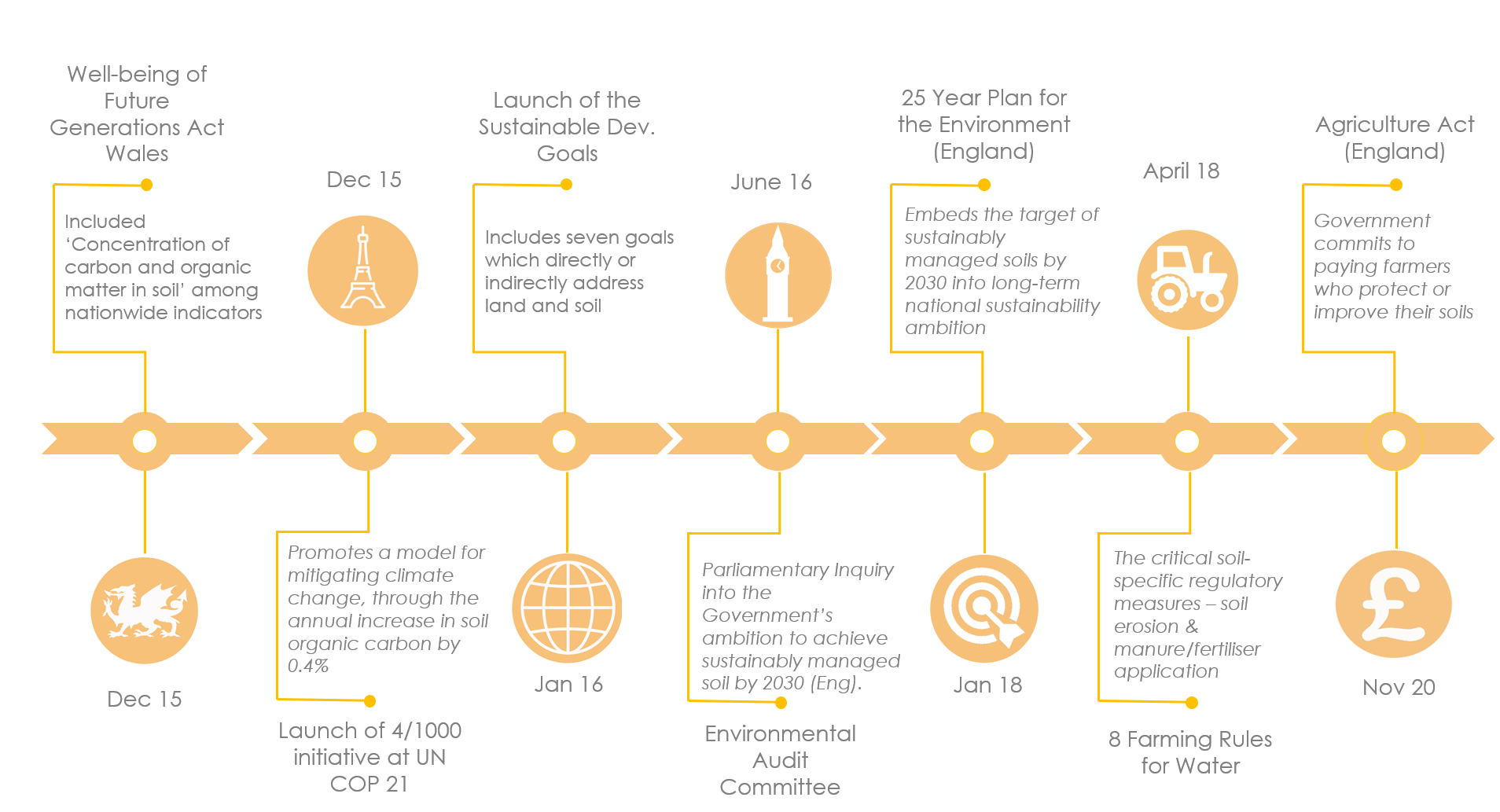

Following Brexit, there are now signs of movement with plans to establish a specific target and set of metrics for the vision of ‘Sustainably Managed Soils by 2030’ (England) under the 25 Year Plan for the Environment – a target which was first established in 2009 in Safeguarding our soils: A strategy for England. In the same year, Scotland published its Scottish Soil Framework - but like the English equivalent, it did not commit to any new policies or investment, but provided a framework for the better coordination of old ones.

Wales does not have an equivalent soils strategy, however, the 2015 Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act required Welsh Ministers to set 46 national indicators to assess progress towards achieving the country’s seven well-being goals, including one on Concentration of carbon and organic matter in soil.